10 Subcultures That Quietly Influence Safety Culture in the Workplace

Understanding Why Safety Culture Depends on Organisational Context

Strong safety culture = safer workplaces. That’s widely accepted across industries. Organisations invest in transformation programs, safety maturity models, leadership training, checklists, and more—yet many still fail to make safety culture truly stick.

Why? Because even the most well-designed safety efforts can be strengthened or undermined by deeper organisational currents—the subcultures that quietly shape how safety is actually lived on the ground. This article explores ten of those hidden subcultures—and why understanding them is the starting point to real and lasting safety culture change.

1. Financial Culture – How Budgeting, Transparency, and Cost-Cutting Shape Safety Culture

The financial culture of an organisation refers to the mindset and approach it takes in managing its financial affairs. It determines how the financial cost of various operational elements is perceived and prioritised.

The key implication for safety culture is this: while the provision of adequate financial and other resources is a clear duty of top management under ISO 45001:2018, Clause 5.1, there is no industry-wide standard defining what constitutes a sufficient safety budget. Nor are safety expenditure figures typically disclosed in public corporate records.

The most common result is that safety practitioners are left to estimate safety resourcing needs with minimal benchmarks. When these are presented in organisations where financial restraint dominates, the outcome is often an under-resourced safety program—and, ultimately, a weaker safety culture.

Major safety professional bodies and industry associations have a role to play in establishing what constitutes a sufficient safety budget—possibly indexed to revenue or value earned. Making this a standard metric reported through financial, ESG, or other mandatory public disclosures would go a long way toward enabling meaningful benchmarking for safety teams.

2. Innovation Culture – How Rapid Change and Experimentation Affect Safety Culture

The innovation culture of an organisation reflects how it approaches new ideas, change, experimentation, and continuous improvement. In fast-moving environments, innovation is often encouraged—even expected—as a core driver of growth and competitiveness.

While innovation can energise teams and unlock value, it also introduces new risks—often faster than safety systems can adapt. This has major implications for safety culture, particularly in organisations that operate on the cutting edge of technology, design, or process evolution.

A rapid pace of change without corresponding adjustments to risk assessments, controls, or training creates gaps in hazard awareness. In these contexts, teams may be trialling unproven solutions in real time, exposing workers to hazards that are not yet fully understood or documented.

Under ISO 45001:2018, Clause 6.1.1, organisations are required to proactively identify and manage risks associated with changes in operations. However, innovation cultures may unintentionally normalise work in high-uncertainty environments without adequate safety buffers in place.

A strong safety culture in innovation-driven settings requires not just risk awareness, but the ability to evolve safety systems at the same pace as change. This demands agile safety leadership, adaptive procedures, and close collaboration between innovation and safety functions.

3. Operating Culture – How Precision, Routine, and Discipline Influence Safety Culture

The operating culture of an organisation refers to the prevailing habits, norms, and expectations in day-to-day work—particularly around discipline, consistency, and procedural adherence. It is often shaped by the nature of the industry, the maturity of internal systems, and how frontline work is structured and supervised.

In environments where precision, repeatability, and attention to detail are deeply embedded, safety tends to be reinforced by operational discipline. This kind of culture supports hazard recognition, structured workflows, and effective control measures—often without explicitly trying to build safety culture from scratch.

However, when operating culture is overly rigid or compliance-heavy, it may suppress initiative or create blind spots where procedural gaps exist. Workers may be conditioned to follow routines without fully engaging with the underlying risks, which can erode adaptive safety responses in dynamic situations.

Organisations are expected to integrate safety into their operational control framework, including routine tasks and non-routine activities. ISO 45001:2018, Clause 8.1 outlines requirements for operational planning and control, ensuring that safety is not treated as an add-on but as part of how work is planned and performed.

A strong operating culture can serve as a powerful foundation for safety—provided that procedures are not only followed, but routinely evaluated, improved, and aligned with real-world work conditions.

4. Performance Culture – When Targets and Timelines Compete with Safety

Performance culture refers to the emphasis an organisation places on achieving measurable results—such as speed, output, efficiency, or profitability. While high performance is essential for commercial success, it can unintentionally undermine safety when the pressure to deliver outweighs the commitment to protect.

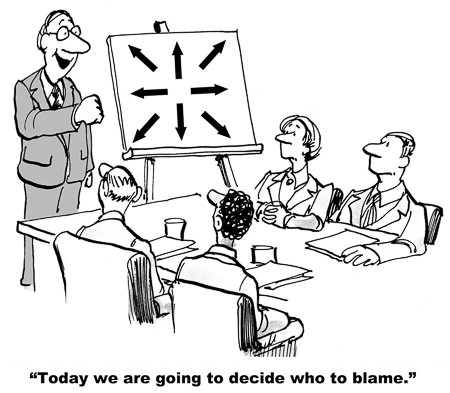

In many organisations, especially those driven by deadlines and production targets, safety may be seen as a potential obstacle to efficiency. This leads to a culture where workers feel they must choose between speaking up about hazards and meeting their goals. Over time, near-miss reporting decreases, shortcuts increase, and safety behaviour becomes reactive instead of proactive.

Performance cultures often reward output without adequately recognising safe practices or the early identification of risk. The implicit message becomes: deliver results first, deal with safety later—if at all.

Under ISO 45001:2018, Clause 5.4, worker participation in safety processes is not optional—it’s essential. However, in a performance-driven culture, workers may be discouraged from participating fully if they believe safety concerns will delay production or draw unwanted scrutiny.

A mature performance culture balances achievement with protection. When safe delivery becomes a core performance metric, safety and productivity can align instead of compete.

5. Risk Culture – How Attitudes Toward Risk Shape Safety Behaviour

Risk culture refers to the collective mindset and behaviours around recognising, accepting, managing, or avoiding risk within an organisation. It determines how risks are perceived, discussed, tolerated, and responded to—often influencing safety outcomes more than formal controls.

A risk-averse culture generally promotes caution, prevention, and careful planning. This type of environment supports a strong safety culture by encouraging proactive identification and mitigation of hazards. However, it may also discourage innovation if not balanced with flexibility.

On the other hand, a risk-tolerant or risk-obsessed culture may normalise exposure to unnecessary hazards. In such settings, taking risks can be viewed as courageous or even necessary to meet performance goals—leading to underreported incidents, unsafe workarounds, and resistance to risk control measures.

ISO 45001:2018, Clause 6.1 requires organisations to identify both hazards and opportunities and evaluate their associated risks. This means risk culture must support open, honest conversations about safety-related risk—especially those that are emerging, unfamiliar, or poorly understood.

A strong safety culture grows from a risk culture that supports informed decision-making, continuous learning, and a healthy respect for uncertainty—without paralysing progress.

6. Leadership Culture – How Presence and Priority Influence Safety Culture

Leadership culture reflects how leaders show up, set priorities, and model expectations across the organisation. It plays a defining role in shaping workplace behaviours—including those related to safety. What leaders emphasise, reward, or ignore sends strong signals to the rest of the organisation.

In a disengaged or aloof leadership culture, safety is often seen as someone else’s responsibility—usually delegated to frontline teams or safety specialists. When leaders rarely visit worksites, don’t engage in safety conversations, or treat incidents as isolated events, it erodes trust and signals that safety is not truly valued.

On the other hand, when leaders are visible, informed, and actively involved in safety decision-making, they build credibility and reinforce safety as a shared organisational value. Workers are far more likely to engage with safety systems when leadership does the same—consistently and authentically.

ISO 45001:2018, Clause 5.1 is explicit: top management must demonstrate leadership and commitment with respect to the occupational health and safety management system. This cannot be achieved through policy alone—it requires presence, behaviour, and accountability.

A strong safety culture depends on a leadership culture that treats safety not as a compliance task, but as a strategic priority—and lives that priority visibly at all levels.

7. Stakeholder Culture – When Pleasing Everyone Undermines Safety Priorities

Stakeholder culture refers to how an organisation manages expectations and relationships with clients, investors, regulators, suppliers, and community groups. These expectations can directly shape decision-making, including how safety is prioritised under competing pressures.

In a "please-all" stakeholder culture, organisations may feel compelled to deliver quickly, cheaply, or flexibly—often at the expense of resourcing or enforcing safety requirements. Safety may be viewed as a cost or delay to satisfying high-priority clients, especially in time-sensitive or budget-driven projects.

The result is often quiet compromises: accelerated timelines, reduced training hours, or safety inspections postponed to meet stakeholder demands. Over time, this erodes internal safety standards and creates a culture where compliance and protection are negotiable.

ISO 45001:2018, Clause 4.2 requires organisations to determine the needs and expectations of relevant stakeholders. But those expectations must be weighed carefully—particularly when they conflict with health and safety obligations.

A mature safety culture requires stakeholder relationships that support—not strain—safety performance. This means educating clients and partners on safety commitments, setting clear boundaries, and standing firm when safety is at stake.

8. Regulatory Culture – How External Enforcement Shapes Internal Safety Behaviour

Regulatory culture refers to the mindset, expectations, and enforcement approach adopted by external regulators and authorities responsible for applying safety laws and standards. It shapes how organisations experience compliance—and how they, in turn, internalise and act on those requirements.

When the prevailing regulatory culture is punitive or blame-focused, organisations may respond defensively, prioritising image management and legal protection over learning and transparency. This can create a risk-averse environment internally, where issues are underreported, and improvement is stifled by fear of consequences.

Conversely, when regulators promote learning, dialogue, and collaboration, organisations are more likely to embrace reporting, engage in root cause analysis, and make meaningful improvements. The tone regulators set has a cascading impact on how safety is led, resourced, and embedded within organisations.

ISO 45001:2018, Clause 10.2 supports a learning-oriented approach to safety, encouraging organisations to investigate incidents constructively and implement corrective actions. But whether organisations feel free to do this often depends on the regulatory culture they operate within.

A healthy safety culture is more likely to thrive under a regulatory environment that values transparency, systemic learning, and continuous improvement—not just fault-finding or legal compliance.

9. Media Culture – How Public Narratives Shape Organisational Transparency

Media culture refers to how workplace incidents and safety-related stories are reported, sensationalised, or framed in the public domain—particularly by mainstream and digital media. This external pressure can significantly affect how organisations manage and communicate about safety internally.

In environments where media attention is intense, critical, or reactive, organisations often prioritise reputation management over learning. Incident responses may become tightly controlled narratives designed to minimise damage rather than uncover root causes. This can discourage openness and foster a risk-averse, image-first internal culture.

Over time, safety professionals and workers alike may become hesitant to report incidents or speak up about unsafe conditions if they fear public backlash or reputational harm. Safety becomes a PR issue, rather than a workforce protection issue.

While ISO 45001:2018 emphasises continuous improvement and transparent reporting, these goals can be undermined when media scrutiny pushes organisations to hide or spin the truth. Trust, both internally and externally, suffers as a result.

A constructive media culture—one that values fact-based reporting and acknowledges systemic complexity—can support a healthier safety culture. Organisations, in turn, should communicate clearly, take accountability, and prioritise learning over optics.

10. National Culture – How Deep-Rooted Values Influence Safety Thinking

National culture refers to the collective values, norms, communication styles, and attitudes shaped by a country's history, society, and traditions. These cultural traits influence how safety is perceived, prioritised, and acted upon—both at the leadership and frontline levels.

People bring their cultural mindset to work. In some national cultures, structure and discipline may drive high compliance and attention to process, while in others, adaptability and improvisation are seen as strengths. Neither approach is inherently right or wrong, but each affects how safety is implemented and understood.

For example, a culture that values hierarchy may result in less upward communication, limiting incident reporting or challenge to unsafe practices. A culture that prizes individualism may encourage initiative, but also risk-taking. These dynamics shape the behavioural patterns that become embedded in the organisation's safety culture.

ISO 45001:2018, Clause 4.1 requires organisations to consider internal and external issues that influence their OH&S management system. National culture is a critical part of that external context and must be factored into how systems are designed and safety expectations are communicated.

A strong safety culture doesn’t ignore national culture—it works with it. Aligning safety messaging, systems, and leadership style with national values enhances relevance, uptake, and ultimately, effectiveness.

Safety culture is never built in isolation—it is continuously shaped by the broader organisational and external context in which it exists. These ten subcultures—financial, innovation, operating, performance, risk, leadership, stakeholder, regulatory, media, and national—each exert a subtle yet powerful influence on how safety is perceived, prioritised, and practised every day. Whether they support or undermine safety depends not on their presence alone, but on how they are balanced, understood, and integrated.

To improve safety culture meaningfully, organisations must first understand it holistically. This means looking beyond policies and checklists and assessing the full context that ISO 45001:2018 places at the heart of its framework. Once the context is clear, organisations can take deliberate, informed steps to shift their subcultures in alignment with safety—making the culture stronger, more resilient, and more deeply embedded.

Safety culturerefers to the collective values, beliefs, and behaviors that shape an organisation's approach to workplace safety.

Within an ISO 45001 safety management system, safety culture is not a standalone clause but is embedded throughout the standard—particularly through requirements for leadership, worker participation, communication, and continual improvement.

- Shapes how seriously safety is taken at all levels of the organisation.

- Influences the effectiveness of safety systems, policies, and behaviours.

- Can be measured, developed, and strengthened over time.

A strong safety culture doesn’t replace systems—it enhances them. It works best when supported by engaged leadership, open communication, and aligned values.

Subcultures in safety culture are smaller, distinct influences within or around an organisation that shape how safety is perceived and practiced. These can include leadership culture, financial decision-making, risk tolerance, or external influences like regulatory and media environments.

ISO 45001:2018 indirectly addresses subcultures through its focus on organisational context (Clause 4), leadership (Clause 5), and worker participation (Clause 5.4), recognising that internal and external factors shape safety performance.

- Subcultures can either support or weaken overall safety culture.

- They often operate quietly, influencing everyday behaviours and decisions.

- Identifying them helps tailor safety strategies to the organisation’s real-world context.

Addressing subcultures is not about eliminating them—it’s about recognising their influence and aligning them with the organisation’s safety goals.

ISO 45001 supports safety culture by placing the “context of the organisation” at the foundation of the safety management system. This context includes the internal and external subcultures—such as leadership, finance, innovation, and regulation—that influence safety performance.

Clause 4 of ISO 45001 requires organisations to understand these contextual factors before designing the system, making safety culture context-specific rather than one-size-fits-all. This principle is reinforced by clauses on leadership (5.1), worker participation (5.4), and continual improvement (10).

- Promotes a system designed around the real-world environment in which safety decisions are made.

- Ensures subcultures are recognised and aligned with safety objectives.

- Creates a dynamic safety culture rooted in relevance, not just compliance.

ISO 45001 doesn’t just outline safety processes—it elevates context as the starting point for shaping a culture that works in practice, not just on paper.

Understanding context is essential because safety culture doesn’t exist in isolation—it is shaped by internal dynamics and external pressures. These include subcultures like leadership style, financial priorities, regulatory expectations, and national norms.

ISO 45001:2018 begins with Clause 4, requiring organisations to identify the context in which they operate before designing or implementing a safety management system. This ensures the system is not generic, but tailored to the realities of the organisation.

- Aligns safety efforts with how the organisation actually functions day to day.

- Highlights cultural influences that may support or undermine safety goals.

- Prevents misalignment between formal systems and informal realities.

A clear grasp of context allows organisations to target root influences and build a safety culture that fits, functions, and lasts.

Subcultures can be identified by observing behavioural patterns, decision-making priorities, language, and informal norms within the organisation. They often surface during safety conversations, audits, interviews, or moments of operational stress.

ISO 45001 encourages this through Clause 4.1 (understanding organisational context) and Clause 5.4 (worker participation), which require inclusive input and real-world insight into how safety is actually experienced—not just how it’s documented.

- Use interviews, surveys, and safety walk-throughs to observe values in action.

- Compare formal safety systems with actual frontline behaviours.

- Address misalignments through leadership dialogue, system redesign, and training.

Identifying subcultures isn’t about criticism—it’s about awareness. Once understood, they can be realigned to reinforce, rather than compete with, your safety goals.

For further insights on building stronger safety cultures, understanding organisational subcultures, and applying ISO 45001 in context, explore our other published content below. If you're looking to enhance your safety performance through data-driven metrics and contextual analysis, visit our Solutions Page to learn more—or sign up for a free trial account and start transforming your approach to safety today.